Students’ perceptions of their psychiatric mental health clinical nursing experience: A personal construct theory exploration

Citation

Melrose, S. & Shapiro, B. (1999) Students’ perceptions of their psychiatric mental health clinical nursing experience: A personal construct theory exploration. The Journal of Advanced Nursing, (30)6, 1451–1458.

Abstract

Personal construct theory and repertory grid technique provides a suitable framework for exploring Registered Nursing students’ perceptions of their psychiatric practicum. This descriptive research was designed to understand students’ own ways of constructing knowledge during their mental health clinical experience. A constructivist conceptual perspective and George Kelly’s personal construct psychology were the theoretical bases of the research. A qualitative case study methodology allowed creation of and reflection on personal construct changes as provided in participants’ review of repertory grid ideas about psychiatric nursing. The participants were six Canadian second year nursing students in a Baccalaureate programme that integrated psychiatric and medical surgical nursing curricula. The following three overarching themes were identified and are used to explain and describe significant features of the psychiatric clinical experience: 1) students’ anxiety related more to feeling unable to help than to interactions with mentally ill patients; 2) students’ feelings of a lack of inclusion in staff nurse groups; 3) student emphasis on the importance of nonevaluated student-instructor discussion time.

Keywords: personal construct theory, psychiatric, repertory grid technique, students’ perceptions, practicum

INTRODUCTION

In this article we describe a naturalistic case study research project that investigated how university student nurses developed personally meaningful constructs during a psychiatric mental health clinical rotation which integrated medical surgical nursing content. The inquiry is grounded in a constructivist approach, where observers are included in the domain of the observed, and the focus is on process and pattern (Novak & Gowin 1984; Candy 1989; Shapiro 1991, 1994; Novak 1993).

Personal construct theory, and the methodology that extends from it, including repertory grid technique (Kelly 1955/1991), provided a framework to listen credulously and to include the voices of student nurses themselves in the project. The psychology of personal constructs honours people as knowing individuals, self-inventors and interpreters of their world (Bannister & Fransella 1971, Shaw 1980, Pope & Shaw 1981, Bead 1985, Fransella 1995).

Most applications of personal construct theory are in the area of psychotherapy. However, the approach also holds considerable promise in the fields of higher education and nursing research. In higher education, Shapiro (1991) used a narrative approach of reflecting upon personal construct changes to explore the ways in which student teachers learned and developed as a result of their practicum experiences in school settings. Fromm (1993) used personal constructs to evaluate what university psychology students learned in seminars on mental illness.

In nursing, existing research guided by personal construct theory and repertory grid technique offers important insights to nurses and nurse educators. In the practice area, the framework provided a forum for community psychiatric nurses and their patients’ and families to collaborate on nursing care and for the nurses to voice their concerns about juggling resources and legitimizing their work (Pollock 1986, 1988, 1989). With nurse administrators, the approach facilitated an opportunity to discuss ideal performance as well as perceived shortfalls in self-performance (Burnard & Morrison 1989, Morrison 1989, 1990, 1991). With critical care nurses, gerontology nurses and general nurses, repertory grids demonstrated differences in the way nurses perceive effective practice and demonstrated the importance of context as an important defining characteristic of nursing (Wilson & Retsas 1997). With psychiatric nurses, general nurses, and mental health social workers, Kelly’s (1955/1991) theory and methods offered a way for each of these professional groups, as individuals, to discuss their perceptions of their roles (Rawlinson 1991, 1995). With novice nurses, the techniques inspired by Kelly have shed light on the feelings of pressure associated with the transition from the role of student to that of new graduate nurse (White 1996). In nursing education, personal construct theory and repertory grid techniques have served as educational tools as well as providing research methodology. In a study by Diamond & Thompson (1985) the approach was useful for learners to compare their own conceptualizations with fellow students’ ideas and the course objectives. Use of personal construct analysis was effective in stimulating personal awareness of pejorative attitudes towards people who attempt suicide (Costigan et al. 1987) and ways of using available resource people in the clinical laboratory (Davis 1985). Awareness of constructs further alerts nurse educators to the possibilities of emerging anxiety and depression (Bell 1990), loss of self-identity, the need for opportunities to reflect and share personal defences (Franks et al. 1994), and inclinations to identify with high-tech medical roles (Heyman et al. 1983) in their students. Finally, the research framework does not necessarily dictate self-congratulatory findings. Wilkinson’s (1982) investigation of hospital diploma student nurses enrolled in their psychiatric rotation revealed that participants’ stereotypical constructions of psychiatric patients as frightening and dangerous people were not altered as a result of a nursing course. The framework has not, however, been used to investigate university student nurses’ perceptions of their mental health clinical experience in programmes of study where psychiatric nursing content is delivered concurrently with advanced medical surgical nursing concepts.

THE RESEARCH APPROACH

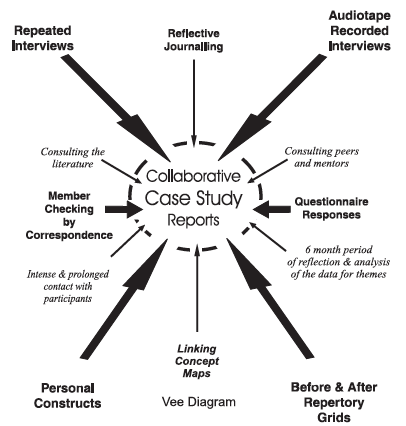

We designed this naturalistic exploratory study to understand students’ own ways of knowing during their 6-week mental health practicum on acute hospital units. The theoretical bases of the research included a constructivist conceptual perspective emerging from George Kelly’s personal construct psychology. Our qualitative methodology used the case study approach to describe the experiences of six Canadian second-year Baccalaureate nursing students from their own perspectives. Data sources included before and after repertory grids (Shapiro 1987,1991,1994), a questionnaire (Perese 1996) and audio tape-recorded interviews. Content was theme analysed (Berg 1995), Vee heuristic diagrammed (Novak & Gowin 1984; Smith 1992) and concept mapped (Colling 1984, Novak & Gowin 1984). (See Figure 1 for a diagrammatic representation of the research process.)

The case studies were written collaboratively with students, and ongoing interaction and member checking by correspondence 6 months after the practicum ended confirmed the trustworthiness and authenticity of the work. The study spanned 3 years, included a pilot project and incorporated the resulting student ‘stories’ into a clinical curriculum. Reflecting on personal construct changes illustrated in the before and after repertory grids, the cornerstone of the investigation, served as both a research and pedagogical tool, and we explain this dual purpose in the following section.

BEFORE AND AFTER REPERTORY GRIDS

The repertory grid technique

The repertory grid technique has been compared to a view or window on the world which invites clients to describe the scenery (Davis 1985). A variety of adaptations have evolved from Kelly’s original grid techniques (Bannister 1985), but the essence of the method is that ‘a grid is a way of getting individuals to tell you, in mathematical terms, the coherent picture that they have of… (whatever subject is under investigation)’ (Fransella & Bannister 1977).

Repertory grid techniques are objective in that scientific systems of analysis do exist. However, they are not mechanically scored questionnaires that yield numerical scores on prescribed traits. They are subjective as forms of the grid permit participants to work with material drawn from their own experience and to comment on such material in their own personal terms. Yet, they do not allow free-ranging, projective responses and interpretations. Pope & Shaw (1981) asserted that grids provide potentially both the researcher and the participants with a means of explaining, monitoring, and reflecting on idiosyncratic (individual) and shared (common) frames of reference that evolve. Shaw (1980) explained that ‘the repertory grid exhibits a “scientific” tool with which to structure a conversation (and) has come to be known as “a hard tool for soft psychologists’” (pp 9).

Devising a repertory grid or repgrid is a unique way of guiding and documenting a conversation. The format should not be seen as a standardized test, but rather as a type of reflective, collaborative interview structure (Pollock 1989). Hermans (1997) described the narrative aspect inherent within the process of constructing and reflecting upon repertory grids as a way of equalizing the playing field between researcher and participant, a way of building a bridge between the expertise of both and a way of valuing the multiplicity of stories which emerge. Discussions that evolve throughout the task do not objectify the participant and they are keenly sensitive to exception. Further, Hermans (1997) emphasized that change, growth and active self reflection is expected as grids are created and re-created. He asserted that the experience can stimulate powerful emotions. In this Dutch psychotherapist’s words: ‘Sometimes we find a drop of tears on the matrix’ (H. J. Hermans, pers. comm. July 8, 1997).

The blueprint to develop a repertory grid involves three distinct stages. The first stage is construction of the grid (that is, creating both elements and personal constructs). The second stage is using the personal constructs to rate, rank, or dichotomize the elements. The third stage is analysis. The explanations that follow detail these three stages.

Stage one: construction of grids

A repertory grid consists of a matrix with elements on the top and constructs down the side of a graph. The elements are relevant people, objects, activities, or concepts in the subject’s experience (Pollock 1986). The constructs are personal bipolar descriptive dimensions that can be applied to each element. For example, in one common form of the grid, and in this study, the elements are supplied by the investigator and the constructs are elicited from the subject.

Elements. Elements can either be supplied by the researcher or elicited with participants. Beail (1985) stressed two important points when selecting elements to be used in grids. First, the elements should be representative of the area to be investigated. For example, in this study, the area under investigation was mental health nursing activities in the psychiatric clinical area of a general hospital where second-year student nurses were required to attend 2 days each week for a 6-week practicum. Secondly, the elements should be within a particular range as constructs apply to only a limited number of people, events, or things. In this case, the range spans common, every-day nursing activities. Students see staff nurses doing these activities and are expected to engage in these same activities themselves. Beail (1985) emphasized that some elements can be outside of one’s existing construct system and therefore cannot be included in the grid. He underscored the importance of giving participants the opportunity to say that they cannot construe a particular element. The elements in this study fit the above criteria, were supplied and were developed in collaboration with a psychiatric nurse colleague and students in the pilot study. The elements are presented in Table 1.

Personal constructs. Fransella (1997) described a personal construct as the ‘unit’ (p.l) of Kelly’s (1955/ 1991) theory and explained that it is ‘a porthole through which we peer to make sense of events swirling around us’ (p.l). She emphasized that a construct is not a concept or a rule and that it has the following main features: it is an abstraction, bipolar, linked to fellow constructs, used at different levels of awareness, the basis of anticipation and prediction and constructs are ways of controlling our world, inseparable from behaviour, inseparable from feelings and can be used effectively within counselling. She summarized the meaning of personal constructs as follows:

The ways in which we experience the world relate to the system of personal constructs we have created to make sense of that world. They are an integral part of the ways in which we behave and feel. Our personal constructs are the ways in which we experience our being. (Fransella 1997, p. 6)

Table 1 Chart of elements or nurses’ activities

- Wearing street clothes on the unit

- Administering a PRN as necessary medication to an agitated patient

- Accompanying a patient on an off-unit smoking break

- Sitting down and drinking a cup of coffee with a patient in the hospital dining room

- Contracting with a suicidal patient to be kept informed

- Denying a noncompliant anorexia nervosa patient’s request to spend time together

- Holding a crying patient’s hand

- Pointing out discrepancies in a patient’s verbal and nonverbal behaviour

Presenting a patient to the healthcare team during unit rounds 10 Facilitating a group therapy session

In the present study, we used triadic elicitation. Here, the participant is asked to look at three specified elements (a triad) at a time, and to say how two of the elements are alike in a way that distinguishes them from the third. The way in which the two are alike defines the emergent pole of the construct and the way in which the other is different is the contrast, or implicit pole (Rawlinson 1991). For example, discussing elements 2, 8 and 6, one student described 2 and 8 as ‘therapeutic’, and differentiated 6 as ‘nontherapeutic’. Another student, discussing elements 1, 10 and 4, described 1 and 10 as ‘professional activities’, and differentiated 4 as ‘personal or social activities’.

Stage two: dichotomizing, rating, or ranking the elements

Once two columns of constructs, with the emergent pole on the left and the implicit pole on the right have been formed, elements are considered individually in relation to each of these pairs of personal constructs and then ranked or rated. Rawlinson (1991) noted that ranking involves placing all the elements in the order in which the construct applies to them. Where rating is used, a three- (trichotomous), five-(as in this study), or seven-point scale is used to indicate the degree to which the relevant construct applies to each element. With some scales, no numbers are apparent to the participants, but numerical values are added by the researcher later. The rating scales, between the columns of constructs, form the rows of the grids. In the present study, all numbers were apparent to participants.

Stage three: analysis

It is important to acknowledge that many forms of complex mathematical and computer analysis of Kelly’s (1955/1991) original techniques now exist. Rawlinson (1991) identified 38 different computer programs used to analyse construct ratings. It is beyond the scope of this article to enter into a discussion of how correlations within the matrix can be analysed statistically. In this case study research, the pre- and postcourse repertory grids were treated as educational tools to stimulate discussion between the researcher and participants and to develop individual case study reports. As in Shapiro’s (1991) work with student teachers, the personal constructs and resulting grids in this study were also used as ‘collaborative tools for reflection’ (Shapiro 1991 p. 123). Because the constructs and grids were developed from participants’ own terms or language, it was the process of discussing and reflecting upon changes in the grids and then searching for themes within the narrative that constituted the analysis. The following three overarching themes emerged from the final case study reports and represent key findings. The first theme was that students’ anxiety related more to feeling unable to help than to interacting with mentally ill patients. The second theme was that students felt a lack of inclusion in staff nurse groups. The third theme was that nonevaluated student-instructor discussion time was vitally important.

THEME ONE: STUDENT ANXIETY RELATED MORE TO BEING UNABLE TO HELP THAN TO MENTALLY ILL PATIENTS

Without exception, at the beginning of their psychiatric mental health clinical practicum, all of the students in this project described feeling afraid of patients on the unit who might hurt them and feeling anxious about their own ability to help. By the end of the rotation, none of the students expressed fear of mental illness and openly shared their admiration and respect for the patients who they met on the hospital unit. This finding was not unexpected and is consistent with many existing studies in psychiatric clinical teaching (Holmes et al. 1975, Marley 1980, Schoffstall 1981, Krikorian & Paulanka 1984, Yonge & Hurtig 1987, Bairan & Farnsworth 1989, Slimmer et al. 1990, Perese 1996, Arnold & Nieswiadomy 1997, Melrose 1998). However, we would also expect students to leave this clinical area with at least a basic confidence in their own ability to help patients who struggle with mental illness. In the present research, narrative from the students’ experiences emphasized that this was not the case. Through conversations about their personal constructs, we discovered that these students left the experience still feeling anxious about their ability to help mentally ill patients. For example, the student who created the constructs of ‘therapeutic’ and ‘nontherapeutic’ rated the elements almost identically on both her before and after repertory grids. This finding illustrates, in part, how she left the course without feeling that she had gained therapeutic skills in the area. Similarly, in several instances, as students used their own words to discuss similarities in the ways they viewed elements at the beginning of the course and again at the end of the course, we were struck by how frequently they commented on an inability to understand how to ‘help’ their patients.

Hospital psychiatric nursing activities often look different from those that students have observed and participated in on other units. First-year nursing courses seldom include nursing care plans for suicidal, hypo- manic or deluded patients. Traditionally, the anxiety associated with incorporating the new and sometimes disturbing knowledge associated with psychiatric nursing dissipated as students completed preclinical lectures explaining the unique nature of the speciality and then became involved with the therapeutic milieu of the unit, joining staff nurse mentors to implement ‘hands on’ nursing care. However, for the students in this study, their integrated curriculum offered limited preclinical introduction to the foundations of psychiatric nursing. With the exception of the provincial mental institution, the short patient stays and acutely ill patient populations on hospital units diminished the possibilities for creating therapeutic milieus. Further, institutional restructuring and downsizing limited staff nurses’ ability to allocate time to mentor students. As a consequence of this combination of circumstances, students in this study found themselves without many of the conventional and reassuring learning resources historically associated with a psychiatric clinical practicum. They were expected to learn advanced medical surgical nursing and optional university courses in addition to their psychiatric clinical requirements and believed that they were evaluated stringently in the clinical area. Thus, looking at the experience through the eyes of these students, we see that the source of their persistent anxiety related to acquiring new helping skills in an environment where the learning resources were ambiguous and not to a fear of mental illness. In response to these kinds of student concerns, it is essential to address learner anxiety in fresh ways, such as introducing psychiatric nursing skills in the first year of university programmes of study.

Through the process of inviting students into conversations about their learning with repertory grids, and by writing their ‘stories’ collaboratively, the present study revealed a different way of conceptualizing student anxiety in the psychiatric clinical area. This perspective suggests a view of clinical teaching where a need for directing students towards acquiring helping skills takes precedence over raising their awareness about mental illness.

THEME TWO: STUDENTS FELT A LACK OF INCLUSION IN STAFF NURSE GROUPS

This research was conducted on hospital units where professional staff were not in a position to integrate students into their working groups. Although they joined practitioners right at their work site and remained there for two 8-h shifts each week for 6 weeks, by the end of the course, none of the students on the three different hospital units felt that they were part of the staff groups. Without requiring orientation to tasks or technological aspects of nursing care, students did not know how to involve themselves on the unit. On medical surgical hospital wards, students, like the nursing staff around them, all wore uniforms clearly identifying how they were part of a common group sharing the task of caring for physically incapacitated patients. However, wearing street clothes instead of nursing uniforms was a new and difficult requirement for all of the students and one which did little to facilitate their feeling of inclusion in staff groups. As students used element 1, ‘wearing street clothes on the unit’, to create their personal constructs at the beginning of the course, they voiced a host of questions related to what they should wear and how they were expected to adhere to psychiatric dress codes. To students, psychiatric staff did not seem to do things the way other nurses did, they did not look like other nurses and their language included a new lexicon of terms drawn from the fields of counselling and medicine. Through the process of discussing repertory grids again at the end of the course, we learned that, although students initially wanted to be included in the staff groups, they did not know how to establish contact, and they were disturbed by some nurses’ lack of professional presentation. Without background information explaining behaviour modification treatment programmes; they found some of the nursing activities related to rewarding only positive behaviours distasteful.

Discussing movement on the construct charts, we found that students did become more comfortable wearing street clothes as the course progressed. However, on a deeper level, we also discovered that time after time, their comments centred on how they continued to feel alienated from staff members. As students co-created case studies from their own interview data and repertory grids, they expressed concern about fulfilling the graded assignments designated by their university course requirements and how they frequently felt uncertain about their place within the unit groups. Eventually, students explained that they no longer even tried to involve themselves in staff groups. Instead, they spoke about how they went their separate ways to create individual situations where they could use their clinical time well. For example, using words from personal construct charts, the first student described how she distanced herself from the nursing unit and ‘studied’ towards her eventual goal of attending medical school. The second turned to a subgroup of peers, naming the time he spent with them his ‘life support.’ The third found a friend and learning partner with whom she could share her experiences. The fourth, intending to practice in the medical surgical area, focused her energy on this more concrete component of the course. The fifth established an important relationship with her instructor. The sixth could not imagine herself becoming a member of a group of hospital psychiatric nurses, even though she expressed interest in pursuing work in psychiatric nursing.

By considering the practicum experience from the student’s perspective, the present research approach leads us to appreciate the difficulties students experience as they grapple with psychiatric nursing concepts. When group involvement was missing for the students in this study, their initial intrigue waned and they became disengaged. Neither the staff work groups nor their clinical groups compelled student attention, but individual grades and assignments clearly did. Designating time and opportunities within the curriculum for students to attend to climate setting and team building within their student groups takes on new significance when we realize that students can feel a lack of inclusion in staff groups in the psychiatric mental health area.

THEME THREE: NONEVALUATED STUDENT- INSTRUCTOR DISCUSSION TIME WAS VITALLY IMPORTANT

When given an opportunity to share their perceptions about personal ways of knowing and expressing understanding through personal construct changes and narrative reflection, the students in this study consistently identified dialogue with their instructors as their most important learning resource and the one which they wanted more opportunities to pursue. By count, students emphasized the importance of nonevaluated discussion time with their instructors the greatest number of times during discussions. From their point of view, few other resources seemed accessible. None of the students felt that their psychiatric nursing textbook offered sufficient explanations of the physician-directed treatment they observed being implemented on the units. While students did mention turning to library resources such as journal articles for their required assignments, they did not find them helpful. One student explained: ‘it’s hard to read them when we don’t know anything to begin with’.

Students were protective of their instructor’s time, noticing how she had ‘seven other students to get to’, and they were reluctant to ‘ask again’ or ‘bother her.’ However, they emphasized that instructor time was their primary resource and commented that they needed more of it. The student who viewed nursing activities as either ‘professional’ or ‘personal/social’ experienced dramatic reversals in her thinking. During nonevaluated conversations with her teacher, she appreciated exploring her ideas about how activities she previously associated with social situations, such as drinking a cup of coffee with a patient, could also be construed as an important aspect of a professional interview. One student explained that his clinical instructor also ‘talked’ with him through her comments in his reflective journal and that he valued this exchange as well. Another student ‘sorted out’ how she could establish personal boundaries with her patients during discussion time with her instructor and expressed how she felt ‘safe’ during talks with her teacher.

Although the clinical instructors all spent time evaluating students and providing feedback on the activities they were required to complete for their course, it was the nonevaluated discussion time that students spoke of when they were asked to describe experiences that were personally meaningful to them. When we consider how disturbing it can be for students to learn about psychiatric nursing, the need for adequate time to debrief becomes clear. The experience of one student, who found herself remembering her own sexual abuse victimization during the rotation, reflects the personal nature of issues that can come up for students as they meet and bond with their patients in this unique clinical area. Similarly, another student also described how a peer disclosed a personal struggle with a mental health problem to her. None of the students in this study escaped feeling ‘touched’ by their patients and each participant found the rotation emotionally draining. Three of the students in this small sample described times when they ‘cried’ after a clinical day. We do not encourage students to discuss clinical experiences with their own friends or families. Clinical conference times can focus on content or the needs of vocal students and university nursing students do not necessarily develop confiding relationships with peers in their clinical groups, limiting the debriefing opportunities available to many students.

Learning about psychiatric nursing is complex. Understanding and accepting personal responses to the speciality is a gradual process and one which requires time and opportunities to dialogue with professionals in the field. For the students in this study, this important dialogue occurred during conversations with their teachers. Constructing personally relevant connections among ideas about nursing activities, physician’s medical treatment and patients’ own experiences with mental illness may not happen if students are preoccupied with tasks required by their course. Although nonevaluated time set aside strictly for discussion may seem frivolous in relation to today’s fast paced clinical nursing curricula, it is important to remember the lasting benefit students attribute to this special time.

DISCUSSION

The aforementioned three themes, developed from discussing changes on construct charts, illustrate how student nurses today face new and complex challenges in their personal process of acquiring psychiatric clinical nursing knowledge in programs which integrate both psychiatric and medical surgical content. In this project, Shapiro’s (1987, 1991, 1994) adaptation of repertory grid technique set a tone of empathy and respect for students’ views and consistently generated opportunities to listen attentively and ground conversations in students’ own words and ways of expressing their thoughts. Listening attentively as students created and reflected on their personal constructs and then developing overarching themes revealed different and important new ways of looking at anxiety, group inclusion needs and nonevaluated time with instructors. Previously, student anxiety in the clinical area was considered to be related to fear of bizarre or aggressive patient behaviour and this anxiety was expected to dissipate, once students came to know their patients and became involved with the therapeutic milieu of the unit. However, the present investigation suggests expanding our ideas about students’ anxiety to include their persistent concerns related to feeling unable to help their patients. In turn, this understanding affirms the importance of addressing students’ expected fear of mental illness, but perhaps more importantly, it can also guide us towards providing students with additional resources which explain current treatment approaches. Similarly, knowing how much students value learning opportunities where they are part of a cohesive group and the times they spend talking with their instructors prompts us to ensure that these experiences are actually available.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have presented a personal construct theory research approach which provided a suitable framework for exploring student perceptions. In contrast to other methods of data collection, that may simply emphasize results, we found that our research approach itself was valuable in generating in-depth information and offering a pedagogical tool to learners. Through the process of constructing before and after repertory grids, we were able to create case study reports collaboratively with each student and then develop common themes. The experience of working together and using students’ own words to articulate their learning and change enabled us to listen in new and meaningful ways to students. We extended existing understanding of what it is like for students during their psychiatric clinical practicum by identifying three overarching themes. In our work, we found that students can be more anxious about helping their patients than about the behaviours which mentally ill patients might manifest, that students felt a lack of inclusion in staff groups and that nonevaluated student- instructor discussion time is vitally important. We call for the creation of more opportunities to listen to students, to incorporate their thinking, and most importantly, to change what we do in response to what we learn about their thinking.

References

Arnold W. & Nieswiadomy R. (1997) A structured communication exercise to reduce nursing students’ anxiety prior to entering the psychiatric setting. Journal of Nursing Education 36, 446-447.

Bairan A. & Farnsworth B. (1989) Attitudes toward mental illness: Does a psychiatric course make a difference? Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 111, 351-357.

Bannister D. (1985) Foreword. In Repertory Grid Technique and Personal Constructs (Beail N. ed.) Brookline Books, Cambridge MA, pp. xi-xii.

Bannister D. & Fransella F. (1971) Inquiring Man: the Theory of Personal Constructs. Penguin Books, London.

Beail N., ed.. (1985) Repertory grid technique and personal constructs. Brookline Books, Cambridge MA.

Bell B.F. (1990) A study of women in transition: becoming a nurse. Unpublished Phd Dissertation, University of Wollongong, Australia.

Berg B. (1995) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Allyn, Boston.

Burnard P. & Morrison P. (1989) What is an interpersonally skilled person? A repertory grid account of professional nurses’ views. Nurse Education Today 9, 384-391.

Candy P. (1989) Constructivism and the study of self-direction in adult learning. Studies in the Education of Adults 21, 95-116.

Colling K. (1984) Education for conceptual learning: A curriculum for educationally disadvantaged baccalaureate pre-nursing students. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Cornell University.

Costigan J., Humphrey J. & Murphy C. (1987) Attempted suicide: a personal construct psychology exploration. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 4, 39-50.

Davis B. (1985) Dependency grids: An illustration of their use in an educational setting. In Repertory Grid Technique and Personal Constructs (Beail N. ed.) Brookline Books, Cambridge MA, pp. 319-332.

Diamond P. & Thompson M. (1985) Using personal construct theory to assess a midwives’ refresher course. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 2, 24-35.

Franks V., Watts M. & Fabricus J. (1994) Interpersonal learning in groups: an investigation. Journal of Advanced Nursing 20, 1162-1169.

Fransella F. (1995) George Kelly. Sage, London.

Fransella F. (1997) Essentials of personal construct theory. Preconference workshop presented at the Twelfth International Congress on Personal Construct Psychology, Seattle, WA.

Fransella F. & Bannister D. (1977) A Manual for Repertory Grid Technique. Academic Press, London.

Fromm M. (1993) What students really learn: Students’ personal constructions of learning items. International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology 6, 195-208.

Hermans H. (1997) Valuation theory and self-confrontational method. Pre-conference workshop presented at the Twelfth International Congress on Personal Construct Psychology, Seattle, WA.

Heyman R., Shaw M.P. & Harding J. (1983) A personal construct theory approach to the socialization of nursing trainees in two British hospitals. Journal of Advanced Nursing 8, 59-67.

Holmes G., Klein L., Stout A. & Rosenkranz A. (1975) Nursing students’ attitude toward psychiatric patients. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 13, 6-10.

Kelly G. (1955/1991) The Psychology of Personal Constructs. Vols 1 & 2. Norton, New York. Reprinted by Routledge, London. 1991 version used for citation purposes.

Krikorian D. & Paulanka B. (1984) Students’ perception of learning and change in the psychiatric clinical setting. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 22(3), 118-124.

Marley M. (1980) Teaching and learning in a psychiatric mental health setting. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 18, 16-21.

Melrose S. (1998) An exploration of students’ personal constructs: Implications for clinical teaching in psychiatric mental health nursing. Unpublished Phd Dissertation, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Morrison P. (1989) Nursing and caring: a personal construct theory study of some nurses’ self-perception. Journal of Advanced Nursing 14, 421-426.

Morrison P. (1990) An example of the use of repertory grid technique in assessing nurses’ self-perceptions of caring. Nurse Education Today 10, 253-259.

Morrison P. (1991) The caring attitude in nursing practice: a repertory grid study of trained nurses’ perceptions. Nurse Education Today 11, 3-12.

Novak J. (1993) Human constructivism: a unification of psychological and epistemological phenomena in meaning making. International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology 6, 167-193.

Novak J. & Gowin B. (1984) Learning How to Learn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Perese E. (1996) Undergraduates’ perceptions of their psychiatric practicum. Positive and negative factors in inpatient and community experiences. Journal of Nursing Education 35, 281-284.

Pollock L. (1986) An introduction to the use of repertory grid technique as a research method and clinical tool for psychiatric nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 11, 439-445.

Pollock L. (1988) The work of community psychiatric nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 13, 537-545.

Pollock L. (1989) Community Psychiatric Nursing: Myth and Reality. Scutari, Middlesex.

Pope M. & Shaw M. (1981) Personal construct psychology in education and learning. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 14, 223-232.

Rawlinson J. (1991) Role related constructions by psychiatric nurses, general nurses and social workers: an exploration of repertory grid technique. Unpublished MN Dissertation, University of Wales, Cardiff, Wales.

Rawlinson J. (1995) Some reflections on the use of repertory grid technique in studies of nurses and social workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing 21, 334-339.

Schoffstall C. (1981) Concerns of student nurses prior to psychiatric nursing experience: an assessment and intervention technique. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 19, 11-14.

Shapiro B. (1987) What children bring to light. Unpublished Phd Dissertation, University of Alberta, Alberta, Canada.

Shapiro B. (1991) A collaborative approach to help novice science teachers reflect on changes in their construction of the role of science teacher. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research 37, 119-132.

Shapiro B. (1994) What Children Bring to Light: a Constructivist Perspective on Children’s Learning in Science. Teachers College Press, New York.

Shaw M. (1980) On Becoming a Personal Scientist. Academic Press, London.

Slimmer L., Wendt A. & Martinkus D. (1990) Effect of psychiatric clinical learning site on nursing students’ attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatric nursing. Journal of Nursing Education 29, 127-133.

Smith B. (1992) Linking theory and practice in teaching basic nursing skills. Journal of Nursing Education 31, 16-23.

White A. (1996) A theoretical framework created from a repertory grid analysis of graduate nurses in relation to the feelings they experience in clinical practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 24, 144-150.

Wilkinson M. (1982) The effects of brief psychiatric training on the attitudes of general nursing students to psychiatric patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing 7, 239-253.

Wilson J. &Retsas A. (1997) Personal constructs of nursing practice: a comparative analysis of three groups of Australian nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies 34, 63-71.

Yonge O. & Hurtig W. (1987) Student identified factors which facilitated learning in a six-week psychiatric nursing rotation. Canadian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing 28, 12-14.